Jonathan Mulki🧉

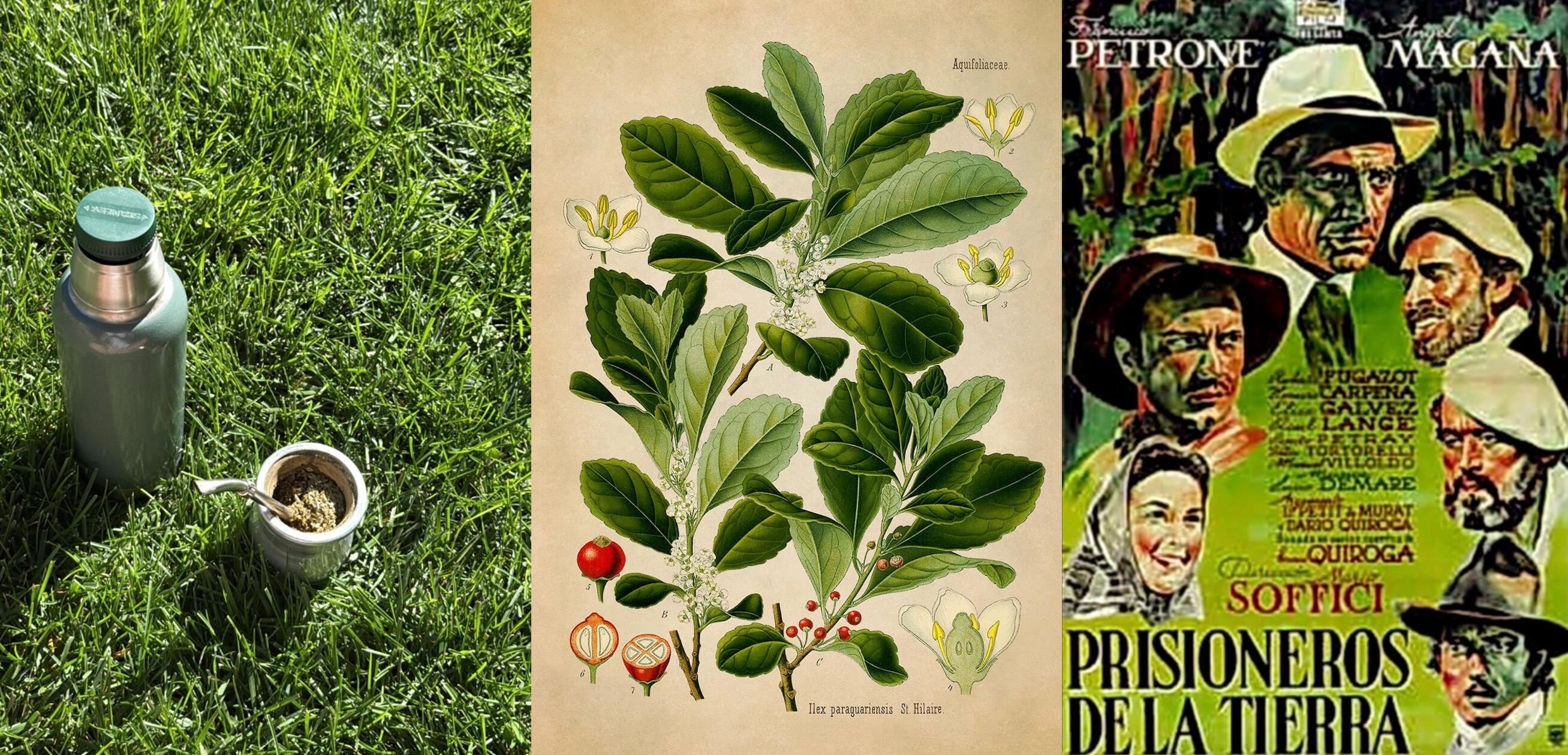

Hello! I'm a PhD Candidate in Latin American Literature at the University of California, Davis, exploring plant-human worlds and environmental humanities. I study cultural representations of yerba mate↗. Thanks for visiting! I hope my work offers something that inspires you, so you can inspire others.

Bio

As an Argentine, I’m a heavy mate drinker thanks to my late grandparents. But ever since I began studying the cultural and ecological histories of yerba mate, I’ve come to see my own culture differently. Perhaps because this plant is older than all of us, even older than our countries, when you look closely at it, familiar ways of seeing begin to unsettle. I’m drawn to the possibilities of insight that nonhuman life can open, and to uncovering the interdependence that moves through all sentient beings.

Research

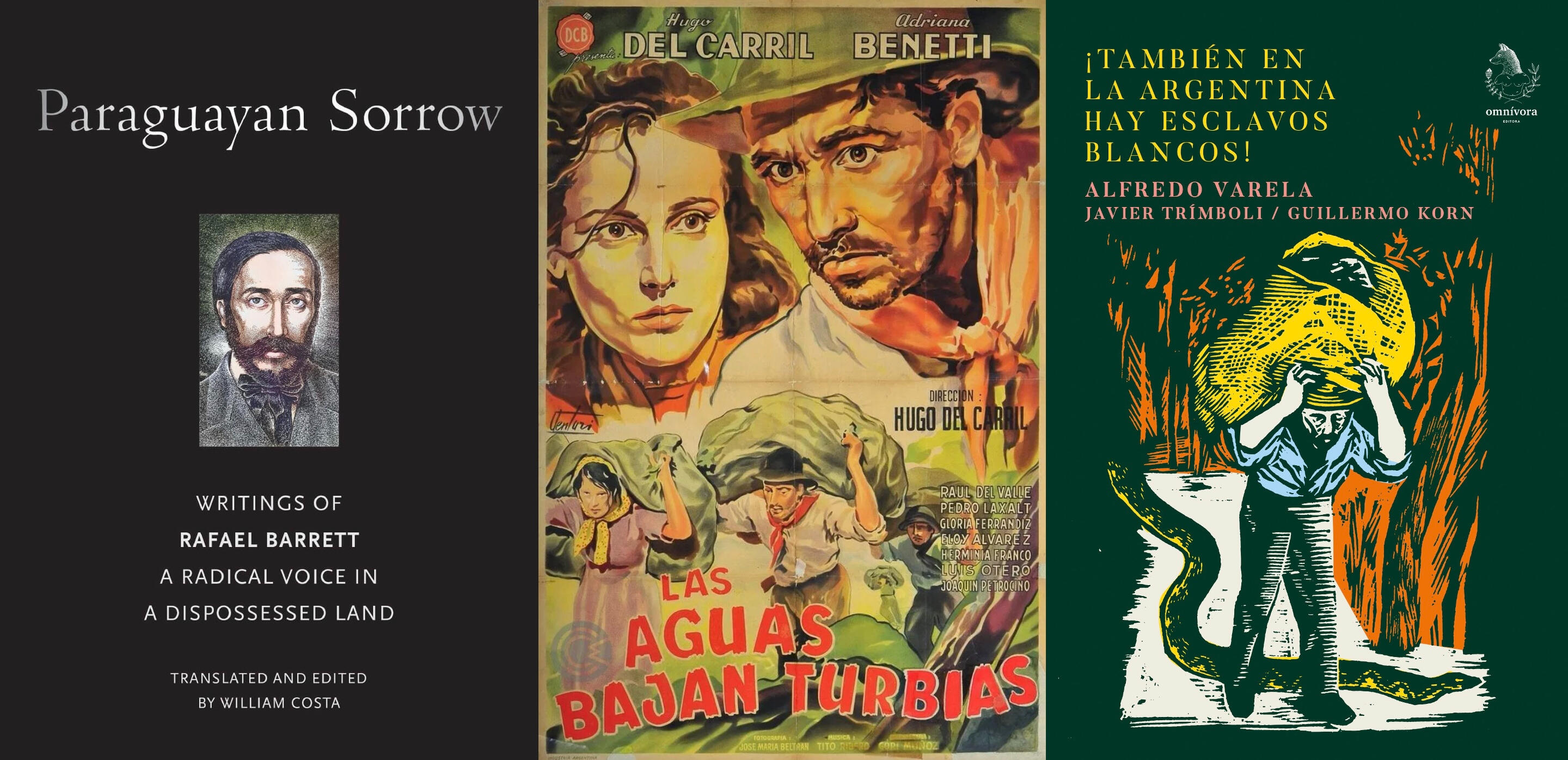

Yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) is the third most consumed caffeine in the world, and also one of the least understood. Across five centuries, this plant has been loved and feared, sacred and cursed, a national symbol and a site of human exploitation. My research explores how literature, film, and art have represented yerba mate as a living mirror of colonial labor, ecology, and identity in the Southern Cone.Few mate drinkers, myself included, grew up knowing the violent histories behind the cup. From the seventeenth century onward, yerba mate was harvested through systems of forced Indigenous labor and later debt bondage, where workers, known as mensú, were sent into the forest for years. These conditions inspired powerful fiction, like Horacio Quiroga’s archetypic 1917 story “Los mensú” or Mario Soffici’s 1939 film Prisioneros de la tierra, which follows harvesters trying to escape the plantations.Today, the wild trees have been replaced by vast monoculture plantations. The system has changed, but its hierarchies remain: yerba still depends on intense manual labor and precarious rural communities. In my research, I coined the term “yerbal regime” to describe this transhistorical, extractive plant–human formation that continually reproduces and refines its own patterns of exploitation. I like to think of it as a living sociovegetal macroorganism, almost a state within the state.I combine literary analysis with fieldwork in the Argentina–Brazil–Paraguay borderlands, documenting the lives, stories, and rituals that continue to shape the yerba world. This work bridges my background in political science with my research in environmental humanities, seeking to understand how plants and the ways we see them carry entire histories within their leaves.

Fieldwork

Many of these cultural works offer striking representations of human–yerba relations, yet they also reveal their historical blind spots: most overlook the Afro-descendant and Indigenous communities that have shaped the yerba landscape for centuries. This omission stems from the enduring tendency to imagine the Southern Cone—especially Argentina—as a creole and white space. To address this imbalance, I combine literary analysis with ethnographic fieldwork, bringing these voices and perspectives back into the stories of yerba mate. In this sense, yerba mate, despite being our national symbol, emerges as a vegetal life-form that can unsettle the very foundations of national identity.During my fieldwork, I visit yerba mate plantations (called yerbales) scattered across the Argentina–Brazil–Paraguay borderlands. Corporate plantations often showcase harvesters working in acceptable conditions for visitors and consumers, but most companies depend on third-party yerbales where labor practices still bear the marks of colonial continuity. In these remote areas, I have documented forms of life that sharply contradict what common sense conceives as basic living conditions. These encounters reveal not only the persistence of extractive systems, but also the resilience and solidarity that allow harvester communities to endure within them.I have also worked with different Guaraní communities in Argentina and Paraguay. I am grateful to the caciques (chiefs) and karaí (spiritual leaders) who welcomed me into their lands and invited me to share mate with them. Few people in Argentina realize that the infusion we drink daily was inherited from the Guaraní, and that each sip quietly continues an Indigenous ritual. During my visits, the caciques reminded me that I am a juruá, a Guaraní term for “white man.” Most of the communities I visited live under constant threat of land dispossession, from both local governments and private investors, always juruás.

Interview

After a month of fieldwork in the yerbales, when I returned to the city, the first thing waiting for me was an interview for the science program NeoCiencia (TV12 Misiones). Local residents had told the producers about my presence and research in the plantations. I was giving seven minutes to share my work and my first impressions visiting different communities in the borderlands.The program wove together excerpts from the films I study with my own footage from the yerbales and scenes from our participatory screenings with harvesters.

Looking back two years later, this interview feels like a snapshot of the beginning, when everything was still raw and new.Watch the interview↗

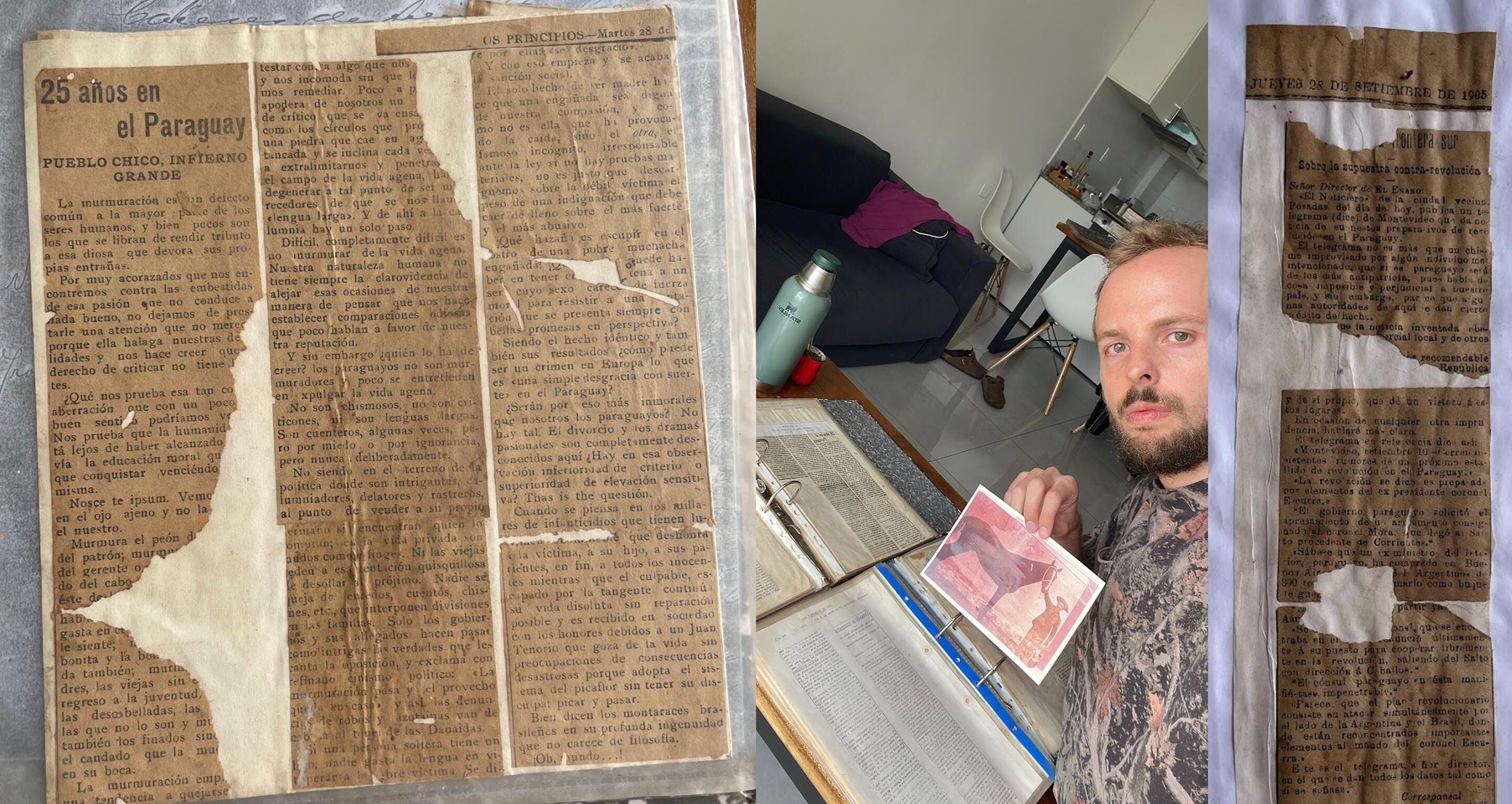

Archival Work

Alongside my research and fieldwork, I am recovering the archive of the French-Paraguayan journalist and writer Julián Bouvier, who appears to be one of the first modern voices to write about yerba mate. While exploring the yerba mate corpus, I kept encountering intertextual references to an author named Bouvier — cited by many of the writers I study — yet I could find no published work or biographical record of him.Eventually, I joined historian Julia Sarreal in her ongoing effort to recover Bouvier’s lost archive, preserved for over a century by neighbors and families in Encarnación, Paraguay. Much of this material survives thanks to the late Paraguayan teacher Osvaldo Salinas, who devoted years to curating it. With the generous help of the Salinas family, I am now working on the curation and critical edition of Bouvier’s writings on yerba mate—a project that bridges archival recovery, literary history, and environmental humanities.There are reasons to argue that the recovery of Bouvier’s archive represents a groundbreaking contribution not only to yerba mate studies, but to Latin American social thought more broadly. Writings about yerba mate—both fiction and nonfiction—span from colonial transatlantic correspondence to contemporary academic work. Yet their most intense historical moment unfolded in the early twentieth century, particularly with the publication of Rafael Barrett’s Lo que son los yerbales (1908).Barrett’s text exposed to the world the hidden structures of exploitation behind the yerba mate economy: modern slavery, the annihilation of local communities, and the complicity of local authorities. His essay shocked the Southern Cone’s self-image as a modernized, civilized region and inaugurated what can be called as the “yerba genre.”Yet recent findings suggest that Barrett was not its founder. Evidence shows that he was, in fact, a reader of Julián Bouvier, whose own writings on yerba mate predate Barrett’s and anticipate many of his ideas. Bouvier died unexpectedly in 1916, and his journalistic texts were never compiled or widely circulated—until now. Today, I am collaborating with an interdisciplinary group of scholars to recover, curate, and publish Bouvier’s long-lost work, restoring a missing chapter in the intellectual and environmental history of Latin America.

Teaching

I began teaching at the age of 21, when I became a full time high school teacher in Buenos Aires. I taught Argentine and Contemporary History, and courses in Ethics and Citizenship. After getting my Master's at Central European University, I returned to Buenos Aires to become a Lecturer in public and private universities, teaching a diverse set of social sciences courses.When I joined the University of California, Davis in 2021, I transitioned to language and literature instruction. As we welcomed the first post-pandemic student cohorts, the focus naturally shifted toward student-centered approaches that prioritized mental health and emotional well-being. Drawing on language acquisition theories that frame negative emotions as barriers to learning, I began designing strategies to transform affective challenges into opportunities for awareness and expression, gradually shaping my own language-through-content approach.Much of my PhD teaching has been in Spanish Composition, where I created a portfolio of what I call “writing performances.” A long-standing daily journaling habit, now more than a decade old, inspired me to integrate reflective and theatrical elements into the course. Influenced by Los Angeles poet Jack Grapes and his Method Writing, which blends writing with acting techniques, I designed assignments that channel emotional release through Spanish as a medium. In this approach, Spanish becomes a tool rather than a goal. Yet, by expressing emotion through it, students often end up discovering a more intimate and confident relationship with the language itself.One of the writing performances I enjoy the most is titled Cuéntale a Lemmy (Tell Lemmy). I came up with the idea one night while watching old episodes of the 1994 TV show Ask Lemmy, where fans wrote letters to the artist Lemmy Kilmister, sharing their secrets and seeking his advice on air. I adapted this premise for the classroom: for the first time in the course, students would write a deeply personal letter—but not submit it, nor read it aloud. The point was to transform the classroom into a completely safe space, where writing itself becomes the act of release.Each time I teach this exercise, several students end up writing, for the first time, about something they had never dared to express before. And they do it in Spanish! Only later did I discover that this approach echoes the well-known therapeutic journaling experiments of Dr. James Pennebaker, which explore how writing about emotions promotes psychological well-being and cognitive integration. My teaching is also informed by my research in environmental humanities. In my upper-division course Creative Writing in Spanish, I explored ways of inspiring students to write about their relationships with nonhuman companions, especially vegetal life.

Future Research

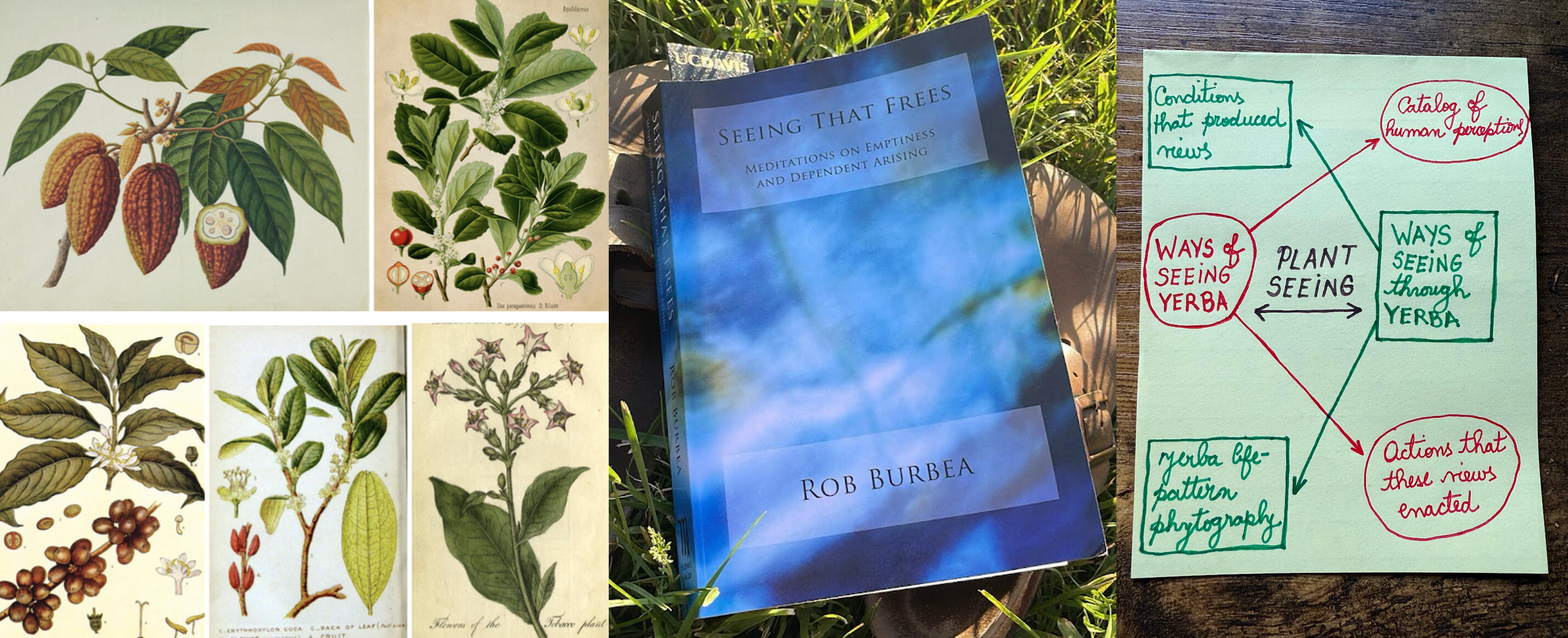

For the coming years, and building on my research on yerba mate, my next project expands into a comparative study of stimulant plants beyond the Southern Cone, including coffee, cacao, tobacco, coca, sugarcane, and pulque. I seek to explore how each plant articulates distinctive entanglements of consumption, ecology, and labor, with particular attention to Indigenous and Afro-descendant epistemologies. I have already designed an upper-division course on this topic, Stimulants in Latin America (see PDF↗), and I look forward to teaching it in the near future.Over the long term, I am expanding my research agenda beyond plants to include perception itself, both as a topic and as a methodology. I was first inspired by the Plant Studies concept of "plant blindness," which names the human inability to perceive vegetal life as part of our shared world. From there, my attention shifted toward perception more broadly, especially theorizing new regimes of visibility that move beyond the Western dualism between “human” and “nature.” I have witnessed the limits of this dualism during my visits to Guaraní communities, where plants are not objects of observation but kin, interlocutors, and teachers.Rather than treating this as ethnographic information, I became interested in the mechanisms of perception that make such experiences possible. I am developing Plant-Seeing as a framework for studying how perception mediates our relationships with the more-than-human world. I am currently using this approach as a reading methodology in my dissertation and look forward to expanding it after completing the Ph.D. If your work connects with these topics, I would be grateful to connect and exchange ideas. Feel free to reach out!

News

— Feb 2026

• Presentating Plant-Seeing at ACLA (Montreal).— Jan 2026

• Presenting PALAC at MLA (Toronto).

• Publication of Plants and Animals in Latin American Cultures.

© 2025 Jonathan Mulki🧉